The media format for the (physical) archive is the two-minute wax cylinder.

The media format for the (physical) archive is the two-minute wax cylinder.

Original Edison phonographs have been employed: a ‘Fireside’ model A circa 1909 and a ‘Triumph’ model B from 1906, for recording and playback respectively. The speed is set at approximately 160 rpm. Any Edison cylinder phonograph may perform both functions simply by exchanging the reproducer for a recorder head, but because of the high amount of swarf shavings produced during the recording process which penetrate the mechanism, a dedicated machine has been used for this purpose.

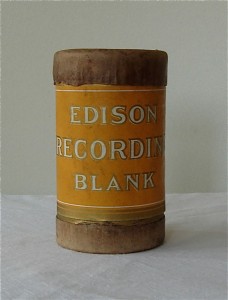

Two types of blank cylinders have been used: those newly manufactured by Paul Morris, which are closely modeled in size and formula after the original Edison brown wax blank cylinders produced between the 1890s – c. 1908, and original oversized black dictation cylinders from the Ediphone Voicewriter or Dictaphone firms and generic brands such as Unity or Nuphonic which were manufactured for business purposes until the 1950s.

The overall size of a dictation blank is much longer and thicker than that used for recording or playback on a conventional phonograph and it is necessary to cut each one down to size with a hacksaw and shave down the surface in order to have a suitable length and diameter to fit a conventional phonograph. An Edison dictation cylinder shaving machine circa 1920 has been used for this purpose. These cylinders are left half an inch longer to allow for additional recording time of approximately fifteen seconds.

The overall size of a dictation blank is much longer and thicker than that used for recording or playback on a conventional phonograph and it is necessary to cut each one down to size with a hacksaw and shave down the surface in order to have a suitable length and diameter to fit a conventional phonograph. An Edison dictation cylinder shaving machine circa 1920 has been used for this purpose. These cylinders are left half an inch longer to allow for additional recording time of approximately fifteen seconds.

The cylinders are gently warmed before recording by using a hairdryer or placing lamp with a 100watt bulb directly over a slowly revolving cylinder. A softer cylinder surface ensures that the cutting stylus meets less resistance as it ploughs through the material, resulting in less noise and a wider frequency and dynamic range. They must, however, be left to cool down before playback.

Recording is achieved using the vertical cut process, also known as ‘hill and dale’, as opposed to lateral, or side-to-side recording more commonly used on disc media. When the groove is being cut, the sound energy from the recording source will vibrate the diaphragm and its attached cutting stylus to varying degrees in accordance with the sounds being made, resulting in a spiral groove consisting of microscopic undulating bumps. Loud sounds will force the stylus to cut deeper, while softer sounds skim the surface.

Where possible, one or more cylinders are used as test recordings and as many as five further recordings per artist are made from which to choose one example for the archive. The remainder are shaved down for re-use. On many occasions however, only one attempt to record a cylinder has been possible.

Two types of Edison recorder have been used, an early ‘Automatic’ type model dating from circa 1892, equipped with a glass diaphragm and original cupped stylus, and also commercially produced models of equivalent design from the early 1900s with mica diaphragms and new, flat-edged sapphire cutting-styli. Mica is more flexible than glass, but the increased sensitivity often results in distortion when louder sounds are played into the recording horn. This phenomenon, termed ‘blasting’ in contemporary literature is much less of a problem when using glass. Glass therefore achieves a more ‘natural’ recorded sound and is the material of choice among experienced phonographers. However, I have tended to use recorders with mica diaphragms in situations were only one recording is possible, as I have found that they can register softer sounds more reliably.

The recording horn is of great importance in the acoustical recording process as it is through this device that sounds are collected and channelled in order to vibrate the diaphragm. Horns designed for this purpose do not possess a flare so as to capture or the sounds without reflections. In addition they are made with a thicker gauge metal than their sound reproducing counterparts and bound with cloth or rope, or covered with papier-mache in order to minimize the horn’s own resonant frequencies.

I have used a custom-made horn modeled on a German original and an authentic English phonograph studio horn circa 1906 some six-and-a-half feet in length.

The recording level can only be monitored by the amount of ‘rattle’ the diaphragm makes when the stylus is out of contact with the cylinder surface, or by touching the tip of the cutting-stylus and feeling the intensity of the vibrations. One can also listen through the recording horn in order to get an impression of the overall balance of what is to be recorded.

The musicians, reciters or electronic devices are positioned close to the mouth of the horn. Groups may be balanced so that the loudest instrument is placed furthest away. Some softer sounding instruments or voices require very close proximity to the horn in order to register at all. If texts are being recited, then the reader is advised to annunciate and speak loudly and slowly, although many have preferred to use an unforceful and more natural-sounding voice delivery.

The phonograph motor is turned on, the mandrel reaches a constant speed and the recording begins when the carriage arm lowers the recorder onto the revolving cylinder. The heat-lamp is left on and the swarf shavings are brushed off during the recording with a small, soft paintbrush to prevent the swarf from clogging-up the cutting-stylus.

Because they are each made by hand, every cylinder will yield a different result, with varying degrees of wow due to defective shaving or overheating, and surface noises or sudden dynamic changes caused by slight imperfections in the mixture and marks on the surface.

Because they are each made by hand, every cylinder will yield a different result, with varying degrees of wow due to defective shaving or overheating, and surface noises or sudden dynamic changes caused by slight imperfections in the mixture and marks on the surface.

All the cylinders have been digitally transferred onto computer hard disc by reproducing them with an Edison ‘N’ large-diaphragm reproducer equipped with a two-minute stylus and recording from a 4.8 ft brass ‘concert’ horn, via an Audio-Technica 4040 large-diaphragm microphone and Pro Tools recording software. Modern audio archivists customarily use light-weight electrical pick-ups with wide tipped styli to record from cylinders, not only to avoid wear on the physical media, but because of the extended frequency and dynamic range made possible through electrical means. In transcribing Phonographies, however, I have sought to preserve the experience of mechanical-acoustic reproduction, from a vibrating diaphragm amplified via a horn to achieve, as closely as possible, an authentic and ‘concert standard’ of playback from the early 1900s.

A.K. July, 2011